China Series

Between 1919 and 1948, all four of my grandparents left their respective villages in southern China and immigrated to the United States. They were told that America was a land of wealth and opportunity, but upon arrival, they faced racism and cultural isolation. After years of hard work and perseverance, they were able to establish livelihoods in the United States. But they always talked about their homeland in a nostalgic way, as if they had left pieces of their souls there.

In 2010, my sister and I traveled in China for two months in hopes of connecting with our cultural and familial roots. My maternal grandparents were able to join us for the trip. Because they were nearing an age when it would be difficult for them to make such a long journey, I knew that it would probably be the last time we would be able to go to China with them.

When we learned that we still had a number of living relatives in the country, we sought them out and spent as much time as we could with them, sharing meals, talking about family history, and visiting the graves of our ancestors. We made pilgrimages to our grandparents’ villages and stood with them in the homes in which they were born. Unfortunately, many of the people my grandma often reminisced about had passed on and most of the places she had frequented had changed hands or been demolished. Yet, in the midst of the poverty that my grandparents had fled, I witnessed an abundance of community and a wealth of cultural practices to honor and preserve family history.

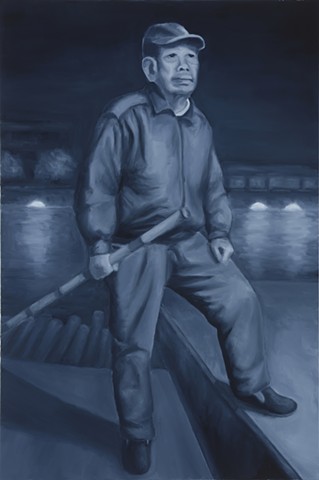

I brought my camera with me everywhere we went and took hundreds of photographs. When I got home, I found myself unable to look at the pictures because they evoked such strong emotions. Like my grandparents, I felt a deep sense of longing for my ancestral homeland. A year later, I decided to make paintings based on these photographs. As the paintings emerged, I found that I was delving into generations of accumulated memories and images, some sharp and others fading. Black and white and sepia toned photographs merged with color photos, creating dull images with spots of vibrant color. The paintings were like selective memory: raw, unencumbered, simple, and vivid, yet inexact.

The time-intensive process of creating oil paintings allowed me to spend time with the images, embed them in my memory, and make them my own. I chose to paint on large canvases to create an immersive environment that would enable me to revisit and reflect on the complex layers of feelings I experienced around the themes of family, migration, and homeland while visiting China as a third generation Asian American.

Today, I live and work in Berkeley in an apartment in which my maternal grandparents once lived. I know that I am surrounded by the spirits of my ancestors who came before me and paved a path for me. As I paint, I understand that this journey is not just mine, but part of a larger collective experience of diasporic people. As my grandparents pass on, I have become the contemporary connection to our homeland. I feel humbled and honored to be the conduit through which my family’s memories pass. I see my role as an artist as ensuring that these cultural and familial ties do not die with my grandparents’ generation. Through these paintings, I hold their memories and restore wholeness to the ruptured self, family, and culture.